Noah Smith, at his Substack blog Noahopinion, posts poll data that shows a precipitous loss of faith in college among a wide swathe of Americans. (https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/americans-are-falling-out-of-love?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email)

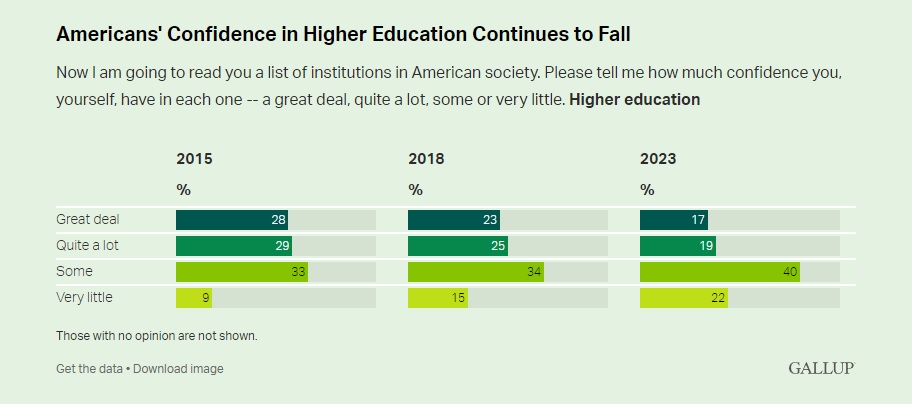

Here’s the grim chart that sums it all up:

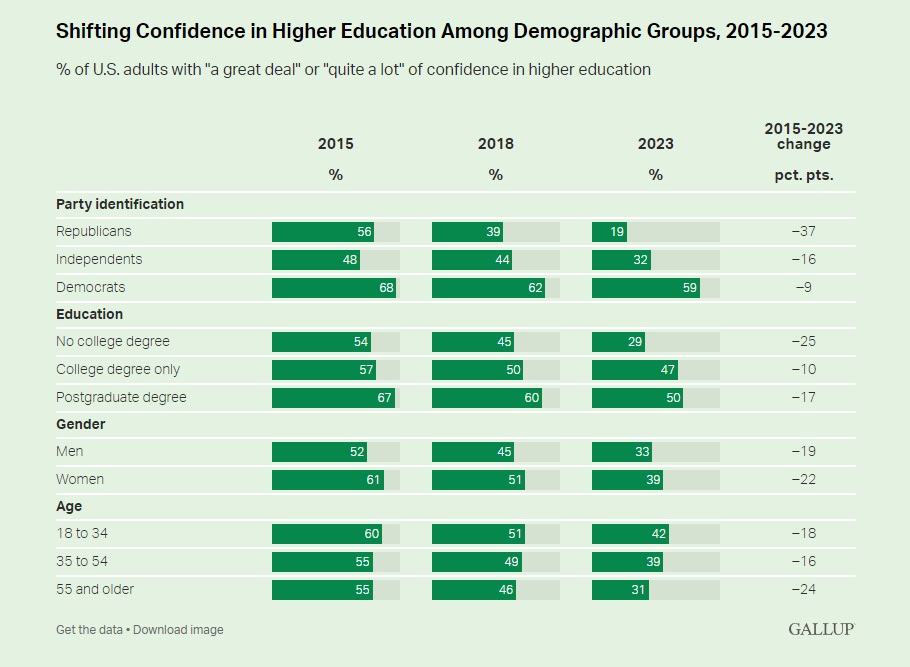

This disenchantment with college is more marked among Republicans—which is no surprise given the profound anti-intellectualism of current day Republican populism joined to the constant attacks upon universities as citadels of liberalism. But Democrats also have much less faith in the usefulness of a college education. Here’s the chart that details the demographic divides on this issue—helpfully giving us the percentage declines since in 2015 in the far right column.

I am just back from the Tennessee mountains where I was visiting with two friends who are English professors at the University of Tennessee. So the plight of the humanities inevitably came up. Which isn’t exactly the decline of faith in college tout court. But is adjacent to that decline.

Anyway, my line was: we no longer have any story at all that we can tell, that feels even remotely plausible, about why someone should be conversant with the cultural heritage represented by the texts of the past. The only rationale anyone ever advances these days is about skills acquired as by-products of reading: critical thinking, pattern recognition, attention to detail, ability to track complex arguments or emotional states complete with competing points-of-view and ambiguous data etc.

Similar arguments are used to justify instruction in writing. Vital communication skills and all the rest.

But even its most ardent practitioners can no longer—in the face of a culture that clearly does not care in the least—make the case for being an educated or “cultured” person, where attaining that status entails familiarity with a cultural heritage marked by certain landmarks, with that familiarity widely shared.

When I taught at the Eastman School of Music, our dean would often lament that the audience for classical music largely consisted of 60+ year olds. What would happen when that audience died off? Well, so far, it turns out that the next cohort of 60 years olds takes their place.

I am currently experiencing something similar. I facilitate two different reading groups (with ten participants in each) of people in their 60s who want to read classics. My sixty year olds in the two reading groups are hungry for encounters with “great books.” Some of the books are ones they read in college and want to revisit. Other selections are books they have always wanted to tackle. So we have read Homer, Dante, Augustine, Dostoyevsky, Joyce, Woolf, Cather, Morrison and Cervantes among others. (Both groups have been going strong for three years.)

Are my readers outliers? Yes and No. They are products of the time when most students were liberal arts majors (English, History, Religious Studies etc.) and then went on to professional careers in business, law, journalism, and even medicine. Like (I would argue) the classical music audience, they had early experiences reading “major authors” (just as the classical music audience had early experiences of learning to play piano or violin and were taken to hear orchestras.) After reaching a certain pinnacle in their professional lives (and after the kids are grown and gone if they had them), these oldsters turn back to the classics. Not everyone in their position makes this turn, but a fair number of people do. They are hungry for the “culture” that they tasted for a while in youth, and now want to revisit it.

The current situation is different because, especially when it comes to books more so that when it comes to music, the early experience is not on offer. A certain subset of the population still gets violin and piano lessons. But fewer and fewer young people are getting Homer, Woolf, or Conrad in either high school or college. There is no early imprinting taking place.

And what are my readers seeking? In a word: wisdom. They are looking for life lessons, aids to reflecting on their own lives. They are just about completely uninterested in historical or cultural context, the kinds of things scholars care about. So the humanities have an additional problem in the context of the research university which is supposed to “produce knowledge.” Why does a society want knowledge about the cultures of the past (its own culture and other cultures) and about its highlighted landmarks? We humanists don’t have a good answer to that one when faced with the general indifference. We can echo the complaints of Matthew Arnold about the philistines who prevail in our society, but we lack his faith that “culture” has something precious to offer that society. And certainly even an attempt to activate Arnold’s vision of “culture” would have little relation to what counts as “scholarship” in the contemporary university. Arnold, too, was mostly focused on gleaning wisdom (“the best that has been thought”) from the classics–although he also hoped that attention to “culture” could provide a “disinterested,” reflective place to stand that would mitigate partisan wranglings. Even in 1867, that last one seemed pretty laughable, and certainly naive.

Still, there was a time when offering wisdom, or paths to maturation, or lessons in the practices of reflection was valued as something college could (and should) do. But such vague values carry no water in our relentlessly economic times. Starting in the 1980s (greed is good) when the gap between economic winners and losers began to widen and it also became clear that there was wealth beyond previous imaginings for the winners, return on investment became all. The decline of support for college is pretty directly tied to a cost/benefit analysis that says the economic pay-off of a college degree has declined.

The facts of that matter are complex. Overall, it’s still a winning economic strategy to get a college degree. It is even unclear whether a degree in a “practical” major like business or health services carries a better economic return than a liberal arts degree in history or literary studies. Determining the facts of this matter are complicated by the extent to which social/economic starting point influences the eventual outcomes along with where one degree is from (given the extreme status hierarchy in American higher education).

But it is simply wrong that college is an economic loser. So why the decline in faith in college? One, the upfront costs are now so much higher than they once were. People go into debt to get a college degree—and the burden of that debt weighs heavily on them precisely when they are setting out and in their most vulnerable, least remunerative years of their job lives.

Second, the relentless attack on what is taught in college for the right wing outrage machine. The strong decline since 2015 registered in the Gallup poll is much stronger among the groups (Republicans and those without a college degree) most susceptible to right wing propaganda.

But we should recognize that the right-wing attack exists alongside a wider and growing sense that college’s sole purpose is job preparation. As a result, much of the traditional college curriculum simply seems beside the point, a waste of time. The degree is what matters; the pathway to that degree is now deeply resented by many students. It is experienced as a pointless, even sadistic, set of obstacles—and the sensible course of action is to climb over those obstacles in the most efficient way possible. (Hence the epidemic of cheating, and the documented increase in the numbers of students who think cheating is acceptable.) What is offered in the classroom is experienced as having no value whatsoever. The only value resides in the degree—a degree that is only slightly (if at all) connected to something actually learned (whether that be some acquired skills or something more nebulous like wisdom.)

We humans seem particularly adept at this kind of reversal of values, making what at first was a marker of accomplishment into the aim of our endeavors. Money becomes the goal instead of a signifier of values, only valuable insofar as it enables access to things needed for flourishing; in a similar fashion, the degree that was simply meant to signify educational acquisition of valuable knowledge is now the goal of the pursuit, with the actual knowledge radically devalued.

Our politicians have acted on this reversal of values. Public higher education is now driven by the imperative to deliver as many degrees for the least amount of public expenditure. That the actual educational outcomes (measured in other terms than simply the number of degrees granted) are devastated by this approach doesn’t trouble them in the least because they buy into the general contempt for the actual content of what gets taught in the college classroom. That the credential (the degree) is divorced from actual competence or knowledge apparently doesn’t bother them either. It’s all numbers driven, with no attention at all to quality.

When we reached this point in this conversation among four English professors (the youngest of whom was 70), we lamented we had become the cranky oldsters we swore we would never become. Spouting the all too predictable: “How it was so much better in our day.” Another blogger I like, Kevin Drum, spends a lot of time debunking the notion that Americans, including young Americans, are worse off today than in years past. (Link to Drum’s blog: https://jabberwocking.com/) When one adjusts for inflation, housing costs and other economic indicators (like wages), things in the United States have been fairly steady over the past 70 years. The key point is that economic inequality has increased. The lower half has mostly held steady, while the upper 20% has taken all of the wealth generated by economic growth over that time span. So the have-nots are not more destitute (they are even slightly better off), but they have to witness the excesses of those who are much more wealthy than they were in the 1950s and 60s.

I think, however, that Drum misses the fact that economic anxiety is way higher, even if that is mostly a factor of the reaction to numbers. To face a monthly rent of $3000 feels more daunting even if that’s only $350 in 1970 dollars. The same goes for college tuition and student loan debts. Especially when college costs have risen faster than the rate of inflation.

So the sheer sticker shock of college costs has to be seen as one factor in the disillusionment. Despite generous aid packages, studies show that the price is off-putting for lower income students—precisely the students least likely to know about how aid works. Add to that the fact that most aid packages also include loans and the upfront financial burdens and risks are daunting.

I used to say there was only three things the world wanted to buy from the US: our Hollywood centered entertainment, our weapons, and our higher education. I think that may still be true, but we sure seem determined to undermine two of the three, leaving only our heavily subsidized defense industry standing. Withdrawal of government support for education (shifting the costs onto students) hurts the one, while corporate greed (screwing the writers, actors, and other workers) hurts the other.

It is a truism that the periods when the arts flourish are also when a nation is most prosperous; think Elizabethan and Victorian England; 5th century Athens; early 15th century Florence etc. The 1950s and the 1960s may not have been such a golden age for artistic achievement, but it was a time of economic well-being. And that fact seems to have generated the confidence that allowed for a non-utilitarian ideal of a liberal arts education to flourish. Yes, that ideal was a “gentlemanly” one, which meant it excluded women, non-whites, and large swathes of the working class. But the GI Bill and the massive investment in public higher education during those years was the beginning of the opening up of that model of college to larger numbers. The retreat from that ideal is not (as Kevin Drum’s work repeatedly demonstrates) the result of America being less prosperous in 2020 than it was is 1965. Rather, it is the fact that completion for a piece of that wealth has been greatly increased. An economy that produced general prosperity (again, with the important caveat that it excluded blacks from that prosperity) has been transformed into one where the gap between winners and losers has widened—and is ever present to every player in the field. (Why do American workers not take their vacation time? Because they are terrified that their absence will prove they are not essential—and so they will be laid off.) The things that our society has decided it cannot “afford” are legion (health care for all; decent public transportation; paying competitive wages to keep teachers in the classroom). Among those things is a college education that has only a tangential relation to a specific job as it aims to deliver other benefits, ones that can’t be easily or directly tied to a monetary outcome.

One thought on “Americans Are Down on College”