I find that I have a bit more to say on the topic of “great books.”

The scare quotes are not ironic—or even really scare quotes. Instead, they are the proper punctuation when referring to a word as a word or a phrase as a phrase. As in, the word “Pope” refers to the head of the Catholic Church. The phrase “great books” enters into common parlance with University of Chicago President Robert Maynard Hutchins’s establishment of a great books centered curriculum there in the 1930s. From the Wikipedia page on Hutchins: “His most far-reaching academic reforms involved the undergraduate College of the University of Chicago, which was retooled into a novel pedagogical system built on Great Books, Socratic dialogue, comprehensive examinations and early entrance to college.” The University of Chicago dropped that curriculum shortly after Hutchins stepped down in the early 1950s, with St John’s College now the only undergraduate institution in the country with a full-bore great books curriculum. Stanford and Columbia had a very great books slanted general education set of requirements for first and second year undergraduates well into the 1990s, but have greatly modified that curriculum in the 21st century.

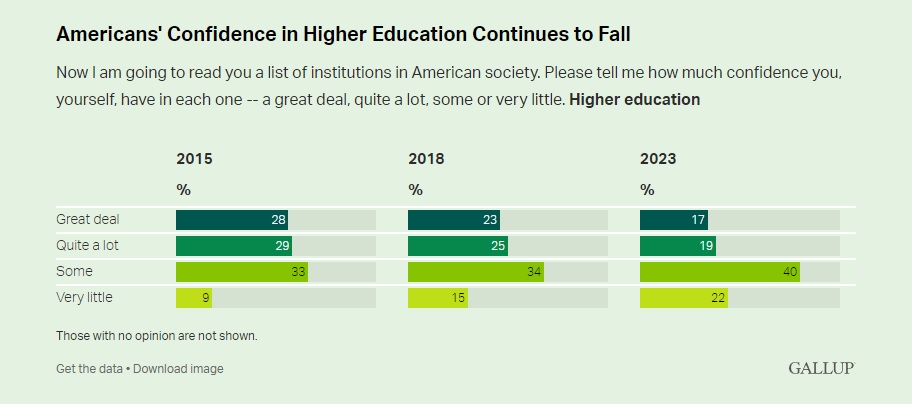

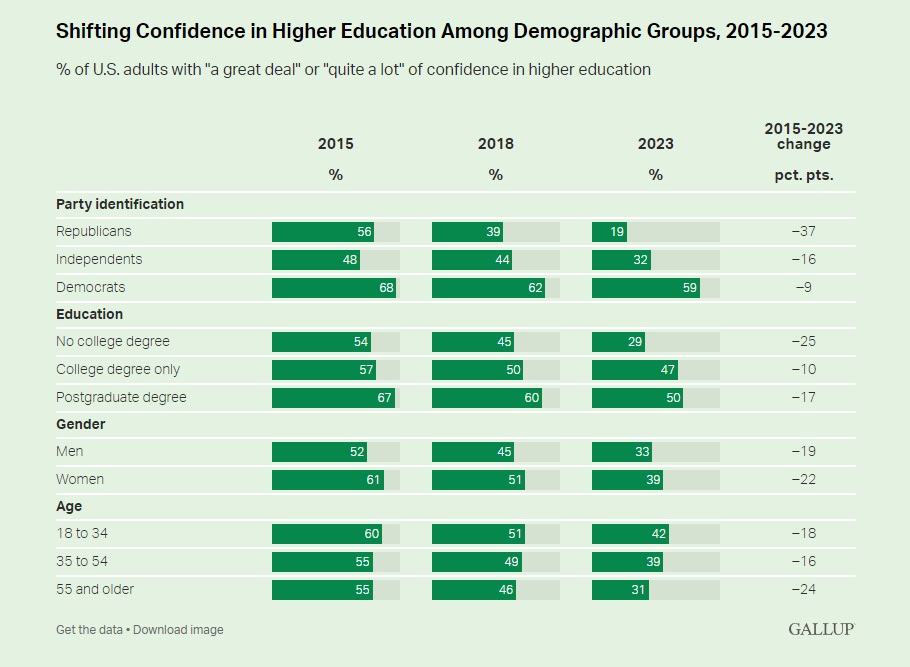

These curricular issues are central to what I want to write about today. “Literature,” Roland Barthes once said, “is what gets taught.” It is very hard to even have a concept of “great books” apart from educational institutions, from what students are required to read, from what a “well-educated” person is expected to be familiar with. As I wrote a few posts back (https://jzmcgowan.com/2023/07/31/americans-are-down-on-college/), we in the United States seem now to have lost any notion of what a “well-educated” person is or should be. The grace notes of a passing familiarity with Shakespeare or Robert Frost are now meaningless. The “social capital” accruing to being “cultured” (as outlined in Pierre Bourdieu’s work) has absolutely no value in contemporary America (apart, perhaps, from some very rarified circles in New York).

I am not here to mourn that loss. As I said in my last post, aesthetic artefacts are only “alive” if they are important to some people in a culture. Only if some people find that consuming (apologies for the philistine word) an artistic work is fulfilling, even essential to their well-being, will that work avoid falling into oblivion, totally forgotten as most work of human hands (artistic or otherwise) is.

Today, instead, I want to consider how it is that some works do survive. I think, despite the desire from Hume until the present, that the intrinsic greatness of the works that survive is not a satisfactory explanation. More striking to me is that the same small group of works (easily read within a four year education) gets called “great”—and how hard it is for newcomers to break into the list. For all the talk of “opening up the canon,” what gets taught in America’s schools (from grade school all the way up through college) has remained remarkably stable. People teach what they were taught.

Yes, Toni Morrison, Salman Rushdie, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez have become “classics”—and are widely taught. But how many pre-1970 works have been added to the list of “greats” since 1970? Ralph Ellison and Frederick Douglass certainly. James Baldwin is an interesting case because he has become an increasingly important figure while none of his works of fiction has become a “classic.” On the English side of the Atlantic, Trollope has become more important while Shelley has been drastically demoted and Tennyson’s star is dimming fast. But no other novelist has challenged the hegemony of Austen, the Brontës, Dickens, and Eliot among the Victorians, or Conrad, Joyce, Hardy, and Woolf among the modernists. The kinds of wide-scale revaluations of writers that happened in the early years of the 20th century (the elevations on Melville and Donne, for example) have not happened again in the 100 years since. There really hasn’t been any significant addition to the list (apart from Douglass and barring the handful of new works that get anointed) since 1930.

I don’t deny that literary scholars for the most part read more widely and write about a larger range of texts than such scholars did in the 1950s and 1960s. (Even that assumption should be cautious. Victorian studies is the field I know best and the older scholars in that field certainly read more of the “minor” poets of the era than anyone who got a PhD in the 1980s or later ever does.) But the wider canon of scholars has not trickled down very much into the undergraduate curriculum. Survey courses in both British and American literature prior to 1945 are still pretty much the same as they were fifty years ago, with perhaps one or two token non-canonical works. More specialized upper class courses and grad courses are sometimes more wide-ranging. Most significantly, the widening academic canon has not moved into general literate culture (if that mythical beast even exists) at all.

The one place where all bets are off is in courses on post 1945 literature. No canon (aside from Ellison, Morrison, Rushdie, Baldwin) has been established there, so you will find Nabokov read here and Roth read there, while the growth of “genre courses” means Shirley Jackson and Philip K. Dick are probably now taught more frequently than Mailer or Updike or Bellow. Things are not as unstable on the British side, although the slide has been toward works written in English by non-English authors (Heaney, Coetzee, various Indian novelists alongside Rushdie, Ondaatje, Ishiguro).

Much of the stability of the pre-1945 canon is institutional. Institutions curate the art of the past—and curators are mostly conservative. A good example is the way that the changing standards brought in by Henry James and T. S. Eliot were not allowed (finally) to lead to a wide-scale revision of the “list.” Unity and a tight control over narrative point of view formed the basis of James’s complaints against the Victorians. The rather comical result was that academic critics for a good thirty years (roughly 1945 to 1975) went through somersaults to show how the novels of Dickens and Melville were unified—a perverse, if delightful to witness, flying in the face of the facts. Such critics knew that Dickens and Melville were “great,” and if unity was one feature of greatness, then, ipso facto, their novels must be unified. Of course, the need to prove those novels were unified showed there was some sub rosa recognition that they were not. Only F. R. Leavis had the courage of his convictions—and the consistency of thought—to try to drum Dickens out of the list of the greats. And even Leavis eventually repented.

The curators keep chosen works in public view. They fuss over those works, attend to their needs, keep bringing them before the public (or, at least, students). Curators are dutiful servants—and only rarely dare to try to be taste-makers in their own right.

I don’t think curators are enough. The dutiful, mostly bored and certainly non-passionate, teacher is a stock figure in every Hollywood high school movie. Such people cannot bring the works of the past alive. For that you need partisans. Some curators, of course, are passionate partisans. What partisanship needs, among lots of other things, is a sense of opposition. The partisan’s passion is engendered by the sense of others who do not care—or, even more thrilling, others who would deny the value of the work that the partisan finds essential and transcendentally good. Yes, there are figures like Shakespeare who are beyond the need of partisans. There is a complacent consensus about their greatness—and that’s enough. But more marginal figures (marginal, let me emphasize, in terms of their institutional standing—how much institutional attention and time is devoted to them—not in terms of some kind of intrinsic greatness) like Laurence Sterne or Tennyson need their champions.

In short, works of art are kept alive by some people publicly, enthusiastically, and loudly displaying how their lives are enlivened by their interaction with those works. So it is a public sphere, a communal, thing—and depends heavily on admiration for the effects displayed by the partisan. I want to have what she is having—a joyous, enlivening aesthetic experience. Hume, then, was not totally wrong; works are deemed great because of the pleasures (multiple and many-faceted) they yield—and those pleasures are manifested by aesthetic consumers. But there is no reason to appeal to “experts” or “connoisseurs.” Anyone can play the role of making us think a work is worth a look, anyone whose visible pleasure has been generated by an encounter with that work.

The final point, I guess, is that aesthetic pleasure very often generates this desire to be shared. I want others to experience my reaction to a work (to appreciate my appreciation of it.) And aesthetic pleasure can be enhanced by sharing. That’s why seeing a movie in the theater is different from streaming it at home. That’s why a book group or classroom discussion can deepen my appreciation of a book, my sense of its relative strengths and weakness, my apprehension of its various dimensions.

So long as those communal encounters with a work are happening, the work “lives.” When there is no longer an audience for the work, it dies. Getting labeled “great” dramatically increases the chances of a work staying alive, in large part because then the institutional artillery is rolled into place to maintain it. But if the work no longer engages an audience in ways close to their vital concerns, no institutional effort can keep it from oblivion.