I have been working my way (painfully slowly) through Raimond Gaita’s Good and Evil: An Absolute Conception (2nd. Edition, Routledge, 2004). It’s a brilliant, fascinating, frustrating, idiosyncratic book. Amazingly right in places, confoundingly wrong in others—and all over the map. I hope to write more directly about its main arguments in subsequent posts.

Right now, however, I just want to use what he has to say (in one of his digressive moments) about treason. Here’s the most relevant passage (for my purposes here, but also for what seems to me his apt understanding of what treason is):

“Treason is a crime against the conditions of political communality. Traitors, by ‘aiding and abetting’ the enemy of their people, help those who would destroy them as a people. Or, they deliver their people and the conditions that make them a people—which enable them to say ‘we’ in ways that are not merely enumerative but expressive of their fellowship in a political identity—as a hostage to the improbable good fortune that their enemies will respect their integrity as a people. Therefore, treason is not essentially, or indeed ever at its deepest, a crime against the state. It is actually a crime against a form of civic association” (253-54).

To wit: treason threatens the very terms of, the very existence, of the civic association that undergirds the state. In reference to Trump: the crime is not against the state, but against the very conditions that make the state possible. That is, one crucial term of American civic association is that the winner of an election gets to hold the office for which that election was held. “We” as Americans can disagree fiercely about all kinds of things, but “we” are no longer a “we” when we do not abide by the results of elections. The state cannot exist if its office holders are not those who have been duly elected. There is no political community left if elections are not respected.

Another point: Gaita’s description of treason holds better for Eastman and Clark (and the others in the Georgia indictment) than it does for Trump. The co-conspirators have aided and abetted the enemy who is aiming to undermine the constitutive civic association. But Trump is the enemy, not one who aids the enemy. He aims to destroy the foundational commonality that makes the political entity called the United States possible.

I could get sidetracked into the legerdemain by which Trump and his followers would insist they are not trying to destroy America, but in fact save it (make it great again). Not worth going down that rabbit hole. But it is notable that they act in a way that would destroy the civic association, while also aiming to keep its infrastructure intact so that there are offices for them to occupy, state functions that they can take over. That’s why there is an argument that their efforts were an attempt at a coup, not a full scale treasonous act whose goal was the utter destruction of a polity or of a “people.”

I don’t know if much hinges on deciding whether Trump and his henchmen are guilty of a failed coup attempt or of treason. In both cases, they are certainly guilty of breaching the constitutive rules of American political and civic life. They have manifestly failed to uphold and defend the Constitution, as many of them swore to do when they took their various oaths of office.

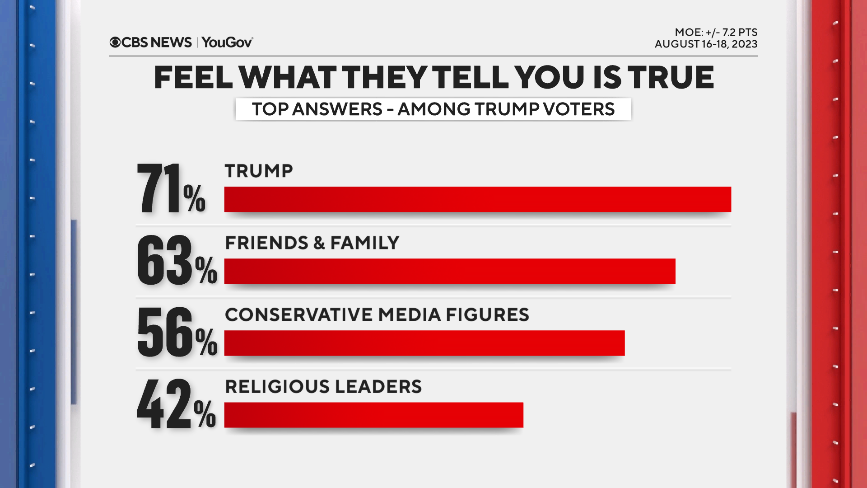

Another side note: the always cogent Timothy Burke has a blog post in which he wonders how anyone with even a modicum of sense would ever go to work for Trump (whose record of treating his helpers dismally is unambiguous and exists in plain sight). Burke doesn’t have any good answers; he can only shake his head in disbelief. Even if Trump is on the rise, no one ever benefits from hitching their wagon to his star. His narcissism can’t abide sharing his triumphs (and whatever fruits those triumphs yield in the way of money, fame, or power) with anyone. Of course, Burke’s puzzlement here only echoes the wider puzzlement over the cult of Trump among such a large share of the populace. This recent CBS poll boggles the mind. Among Republican voters, Trump is deemed more honest than everyone else in their lives by large margins. (Even more than intimates, although the gap there is much lower. Only 8% trust Trump more than their family members.) So much for Hannah Arendt’s sophisticated take on the general cynicism generated by authoritarians, that is, the notion that everyone knows they are lying, but just think “everyone lies” and shrug. No: the lies are believed; they are deemed the only truth out there. (See NOTES below for references.)

But back to Gaita. Because treason (on his take) “undermines . . . the conditions which make it possible for a people to speak as a people, . . . the most fitting (though not, any more, practical) punishment for unrepentant traitors . . . is banishment” (257).

What a lovely thought! I don’t actually see why banishment is “not, any more, practical.” Surely we could send Trump abroad—wonderful to think he would flee to Saudi Arabia—and then keep him from re-entering the United States.) In any case, since banishment is not on the table, let’s at least indulge our fancies in thinking how appropriate the penalty would be in Trump’s case. What he craves is admiration and adulation. Deprive him of his audience, of the “people” to whom his plea for attention is made, let him fulminate in the emptiness of cyber-space entirely outside of the context (an actual civic association) to which his tweets are addressed. Delicious. The punishment would fit the criminal (and, possibly, also the crime) in a Dantesque manner.

NOTES

The Timothy Burke blog post on Trump’s henchmen.

The CBS poll: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-poll-indictments-2023-08-20/

Here’s the most relevant finding in that poll, but it’s very much worth looking at the entire poll results (available through the link).

Finally, the relevant Hannah Arendt passage that has been making the rounds over the past eight years as pundits and others try to come to terms with the phenomenon of the Trump cult:

In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and nothing was true… The totalitarian mass leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that, under such conditions, one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness. (From The Origins of Totalitarianism)

Arendt’s take has proved both too sophisticated and too optimistic. What we have seen instead is that no amount of “irrefutable proof” will lead the cultists to recognize the lie as a lie. The cultists don’t have to retreat to the redoubt of cynicism. They just double down on their belief in the original lie—and in the figure who propagates the lies.

There is a difference in being the enemy of the established government and being the enemy of the people. At some point the people’s interest is counter to government. If the people win, the leader of the traitors becomes the father of the new country. George Washington is an example. His side won

LikeLike